One in 10 Australian adults is experiencing “significant eco-anxiety”, says the Black Dog Institute’s Chloe Watfern.

It is surprising how many people can identify with an experience of climate distress that they might not have realised they were experiencing.

Dr Chloe Watfern, Black Dog Institute

Concerns for the environment are impacting people’s “ability to get up in the morning”. Young people, especially, are grappling with “how to be human” as the planet changes rapidly, Chloe told an engaged audience at the AdaptNSW 2023 Forum.

Chloe, a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Black Dog Institute, is focused on the intersections between mental health and climate change. She shared research published in the Lancet which found more than 80% of 16- to 25- year olds are worried about climate change. Upwards of 45% of young people said their feelings about climate change negatively affected their daily life and functioning, and “75% said the future was frightening to them”.

Closer to home, a 2022 survey of nearly 19,000 young Australians aged 15 to 19 found teenagers feel “helpless” and “anxiety-ridden” about the future. More than a quarter (26%) were “very concerned” or “extremely concerned” about the climate crisis, and 38% of said they had experienced high psychological distress.

A range of terms attempt to explain what many people are experiencing, Chloe noted. Solastalgia describes “the feeling of homesickness that you have when you are home” and no longer recognise what you see. Pre-traumatic stress captures intrusive and intense visions of future. Ecological grief is a sense of mourning for ecosystems, biodiversity and species lost to environmental damage.

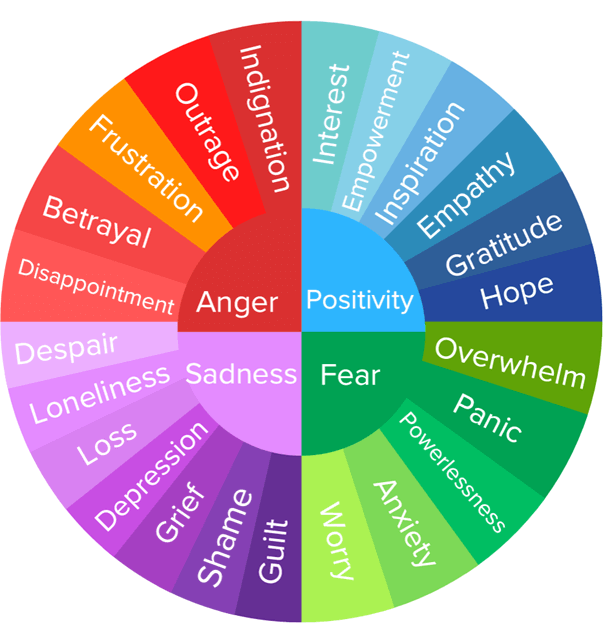

The broad term climate anxiety is a “very valid response to what is a very real threat” but Chloe prefers the phrase “climate distress” because “our climate is in distress”. Acknowledging this “enables a more complex understanding of the emotional responses we might have to climate change. Anxiety might be part of it. But apathy or anger or sorrow are also in the mix of feelings we might have.”

Researchers have developed the ‘Climate Emotions Wheel’ to help people interpret and interrogate their feelings – and this is exactly what the audience did at the AdaptNSW 2023 Forum.

Exhibit 1: Climate Emotions Wheel

People and planetary perspectives

Climate distress challenges “conventional notions” of mental health as an individual problem that someone might solve for themselves, or with the help of a clinician, Chloe said. Climate distress must be understood in individual and collective or “planetary terms” because “we are all in this together and this is all connected”.

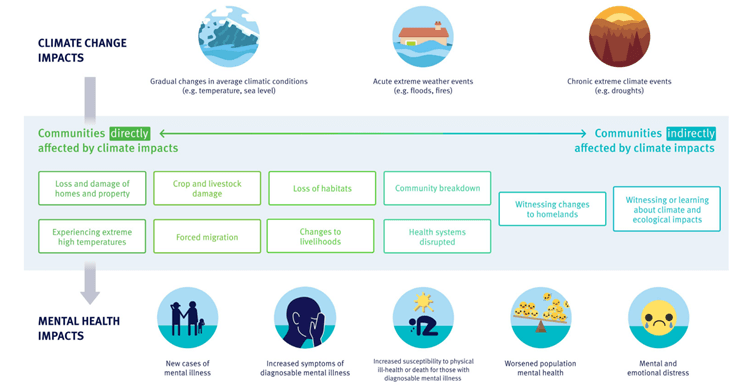

People are experiencing a “spectrum” of mental health impacts. The Grantham Institute at Imperial College London has suggested this occurs in a “continuum”. For example, climate change impacts (illustrated in the top row of circles in the image below) include rising temperatures and sea levels, and extreme weather events such as floods or droughts. This leads to mental health impacts (depicted in the bottom row of circles) including new cases of mental illness, mental and emotional distress, and increased susceptibility to physical illness or death. This occurs directly, such as living with chronic extreme high temperatures or losing a home in a bushfire or floods, and indirectly, when someone watches a natural disaster unfold on TV.

Exhibit 2: The continuum of climate change impacts on mental health

We need to connect to each other but also to the places we are working so hard to protect.

Dr Chloe Watfern, Black Dog Institute

From anxiety to action

How do we respond? How do we look after ourselves and each other?

There are several steps people can take to build psychological resilience. Chloe unpacked research from United Kingdom in 2018, which suggests people move through a “cycle of psychological engagement”. This begins with an “epiphany” about the enormity of the climate crisis that catalyses action and sparks “immersion” in the issue. Typically, after a period of immersion, people reach crisis or “burnout” before moving to a sense of resolution and “agency”. People transition between phases depending on their emotional state and what is happening in the world, Chloe said.

Maintaining a sense of equilibrium is enabled by a “clear vision of a valuable future”, a “sense of proportion”, access to a “cohesive community” and self-care, and by moderating the “level of engagement” so the feelings of climate despair aren’t all-consuming.

People don’t need to manage their feelings in isolation, but instead can tap into “networks of practice of self-care” Chloe said, pointing to peer-to-peer organisations, such as climate cafés that encourage people to connect and debrief.

Climate change can feel “colossal and overwhelming” but “people do build connection through their shared experience of climate distress,” she said.

Connecting with nature can also provide solace and a sense of purpose. Chloe quoted Aunty Rhonda Dixon-Grovenor, a Darug and Yuin Elder, academic, cultural activist and champion for environmental social justice, who tells people to “walk in beauty”. “Go and be happy and joyous in that beauty because if we are in nature and enjoy it and care for it, then it nourishes us,” Aunty Rhonda has advised.

Another strategy is to embrace “active hope,” Chloe said. This is not a “get out of gaol free card” but recognition that hope is “something we do” rather than something that we have . “If we can find ways to do meaningful work for a just and healthy planet – work that also sustains us and provides moments of joy and connection –that offers the hope that so many are struggling to find.”

To access support for climate distress in Australia, visit Psychology for a Safe Climate’s Climate Feelings Space.

AdaptNSW 2023 Forum

The AdaptNSW 2023 Forum, ‘navigating uncertainty together', attracted 350-plus attendees who heard from more than 85 presenters across 30 breakout, panel, workshop and keynote sessions in December 2023. Check out the program highlights and watch recordings of key sessions.